This is a great new innovation in book discovery - the website is called Shepherd.com and the way it works is that authors tell you a little bit about their book, and then recommend five more in the same genre. My first list is for Power Burn and with it my top five books featuring extreme sports...

Thanks to all the lovely people making this happen and I wish them all the best with their new venture!

Facebook and free speech

Free speech absolutism – the idea that anyone can say anything – has had some serious consequences; hate speech, bullying and repression. All of these are a blight on our society. While the majority now holds that some things should remain unsaid, what we cannot agree on as a society is what those things are – where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable speech?

Read MoreSome thoughts on modelling

One of the most controversial aspects of the British Government’s response to the Coronavirus crisis has been its reliance on modelling of the pandemic. There have been suggestions that Boris Johnson preferred to listen to experts in this arena, rather than to those in more traditional branches of public health. In the end, the Government’s strategy changed but there will be many questions to be asked of the UK’s initial reliance on modelling and the efficacy of those models.

This is not the first time that predictions generated by computer models have hit the headlines, just think about climate science – all the predictions of our collective climate future are based on models. These headlines don’t always do us any favours. The Oxford University study that created headlines reporting half of the population could have been exposed to the virus seemed irresponsible in the manner of its reporting. If half the population had already been exposed and so few were sick what was there to worry about? It turned out there was a lot to worry about as this result was generated by an extreme set of initial assumptions.

I’m currently writing a book on strategy and this potential for dangerous news stories was one of the reasons why I’d been thinking about modelling as part of a chapter on risk assessment. I’d concluded that if there is one thing that would improve our ability to assess risk, then it’s to acquire a better understanding of the flood of predictive data coming from models and algorithms. A basic competency with how data sets are collected and analysed, and how the conclusions are reached and presented is absolutely fundamental to good risk assessment and to making good decisions in the modern world.

A model is some — admittedly often complex — maths that calculates an outcome based on the best thinking available in whatever area we are trying to predict. I’ve used modelling a lot in my professional life as a race boat navigator with software that predicts the optimal route in changing weather.

The first thing to point out is that the weather routing software doesn’t predict the probability of an outcome. It doesn’t do risk assessment. It doesn’t output; “the chance of a top three position is 40% on the northern route, and 60% on the southern route”. Instead, it just shows the fastest way to sail from A to B based on the parameters (weather and accompanying boat performance) that it’s given. It doesn’t assign a probability to the chances of this outcome being correct for a very good reason — in the limited world view of the model there is no uncertainty. For instance, it doesn’t compute the possibility of the boat being damaged in particularly bad weather.

And that’s the first point I want to make about modelling — the algorithms very rarely if ever take everything into account. This is the first problem and the very first question that needs to be asked when presented with the output from any model that’s predicting the future;

Does the prediction include the influence of everything that might affect the outcome?

In the case of the weather routing software the answer is definitely not; apart from not taking into account the chance of damage, it also makes assumptions about the boat speed in different wind conditions. The results are also dependent on the accuracy of the weather forecast – and I’m sure we’re all aware of its limitations. Who’s not left the house without an umbrella or jacket and needed both before the end of the day? There are many good and well understood reasons why weather forecasts are inaccurate. These throw light on more systemic problems with many of the other things we try to model.

Firstly, the atmosphere is an incredibly complex system with many different variables; temperature, pressure, humidity, wind speed, wind direction and so on. The models must combine all these variables in complex calculations based on our understanding of the physics that controls their interaction. Unfortunately, we still don’t completely understand all the physics of the atmosphere. We’re getting better at it, but there are still many questions to be answered. So the next question for our model is;

Is the science behind the prediction mature, well understood and accurate?

Of more concern is that even if we did completely understand all these processes down to the molecular or atomic level, we still couldn’t model the weather perfectly because we can’t capture enough detail in the starting conditions. We are getting better at this with satellites, weather balloons, aircraft and drones all adding to the traditional stalwarts of global met data collection — the land stations and ships — but it’s still a far from complete picture. And if we don’t know the full set of starting conditions and know them accurately then our predictions will have limited accuracy.

This is generally true; the bigger the data set the better. Any experiment repeated a thousand times is more likely to provide an accurate answer than one repeated five times. However, resources are not infinite, and no one is going to collect data indefinitely. So data sets will be limited, and we have to decide whether the size of any particular data set is sufficient for the analysis to be credible.

It’s also true that there are many more ways to generate bad data than there are to get good data. If instruments are involved, they need to be an adequate quality, properly calibrated and maintained. If people are involved then anything that they report themselves, by filling in a form or survey is less reliable than that obtained by experiment. And experiments with people are better when they are double-blind (so both experimentor and experimentee are unaware of what’s being done and to whom), and randomised (so the experimental groups are selected at random) to limit the chance of confounding variables. So, the next question to ask of any prediction that you come across is;

Is any data used accurate and comprehensive enough to provide a useful prediction?

It would be bad enough if this were it; but there is an even worse problem for weather forecasting (and some other predictions) in the so-called butterfly effect, an idea developed by an American mathematician and meteorologist called Edward Lorenz, who came up with Chaos Theory. Chaos Theory describes dynamic systems that are particularly sensitive to the starting conditions, so in weather terms, the classic example is a butterfly flapping its wings. This tiny effect subsequently influences the creation of a tornado several weeks later, as it ripples out into the atmosphere.

It’s not just that a tiny change in the atmospheric starting conditions can radically alter the outcome, but that even with perfect knowledge of every single molecule in the atmosphere at any given moment in time, we still couldn’t forecast the weather completely accurately because we can’t control all the butterflies, birds, people, animals or volcanoes that can influence the outcome as time goes on.

So in the case of the weather forecast and many other unstable systems, what we understand from the mature science is that in fact there will always be limitations on the accuracy of the predictions. So we can add one more question;

Does the science behind the prediction envision and allow for a completely accurate answer?

These four questions make a good first test when you see a prediction that’s been generated by a forecaster. In the case of a claim that there is a fifty percent chance of rain today, the answer to all four questions is no – and yet as a navigator I rely almost completely on the weather forecast to develop a strategy. And this is one of the most important points about models; if you are familiar with them, understand the limitations and assumptions then even bad models can be helpful – but when you don’t they can be dangerous.

The problem is that we are all exposed to modelling data that could have a potentially huge impact on our lives – so the four questions are intended to provide a way to deal with that data, to get some sense of its value, and work out how to treat it when we have no expertise in that area. I have zero healthcare or epidemiological knowledge, and yet as the outbreak gathered momentum in the news cycle, I needed a way to assess the predictions that were making headlines, to make a judgement on how to act. So I applied the four questions to the Coronavirus models.

Does the prediction include the influence of everything that might affect the outcome?

No. It was easy to find an example of something that wasn’t included – we don’t have any idea whether there is a seasonal element to transmission of the virus.

Is the science behind the prediction mature, well understood and accurate?

Epidemiology appears to be a well-resourced and mature discipline – however its need for assumptions about human behaviour will always mean there is room for doubt, and some people appear to even question its status as a science.

Is any data used accurate and comprehensive enough to provide a useful prediction?

No, not at this stage of the pandemic. For one thing the amount of testing is massively variable from country to country which completely undermines the data on the number of confirmed cases, and even the number of deaths is prone to errors from uneven reporting.

Does the science behind the prediction envision and allow for a completely accurate answer?

Probably not; chaos theory is a consideration in epidemiology, and I found some evidence that some systems are susceptible to chaotic outcomes.

These are the answers I came up with after half an hour on google as the outbreak gathered pace in the news cycle. The references I found seemed credible to me, but I’m not vouching for them. In my opinion -- and when it comes to working out how the outbreak affects me that’s the one that counts -- they were good enough to reach a conclusion. In this case, I felt that I shouldn’t put too much weight on the modelling, not least because there was a far better data source; the news bulletins out of China, Italy, Germany and Spain. It was very clear which public health strategies were working and which weren’t -- the best data was the real-time experiments being run in the countries that got it before us.

It seemed clear that the British Government’s strategy was wrong and that minimum social contact and – where possible – isolation was the best individual response. It felt almost inevitable that the NHS would be overwhelmed. It was going to be a bad time to get sick, and the priority for a few weeks at least was to stay well.

Fortunately, the Government changed its strategy and this is partly because my reaction was far from unique. The UK public and business response led the political leadership right up to the big U-turn on 23rd March. While there’s evidence that the output from high quality modelling was useful in the hands of professionals who understood what they were dealing with, it’s a tragedy (but hardly a surprise) that Boris Johnson and his leadership team weren’t among that number.

An entry from the notebook - character

These thoughts started out as notes to clarify my own thinking on the fundamentals of writing fiction. They developed a bit more of a structure when I taught a creative writing class at the local art gallery - it was a fun thing to do, but when the gallery closed the class did too and so I thought it was about time these notes found another outlet. This is the second of these blogs, the first was on Point of View and is here.

Definition

The protagonist is the central character that carries the story - the hero.

The idea, the protagonist and the line of action are all integral to the story, it's hard to work with one without the others, and none of them need come first.

The Foundations of Character

How do we begin to create interesting, believable characters?

Characters are defined by what they do and say, not what the writer tells us about them - this is why the line of action is so important. It gives the character something to do and allows the reader to get to know them.

Motive is not essential to either a character or a story, a genre thriller can just be a dazzling sequence of action set pieces. But motive does give the action moral value and makes the character more realistic, particularly if the motives are complex and not black and white.

The easiest starting point is a character 'type'. Is the character a detective, a single man looking for a girl, a spy, the head of a failing business, a husband having an affair... these are all instantly recognisable types. And your protagonist will probably be one of these types, or another like it.

If you start with a type, the reader will immediately stereotype that character - we just can't help stereotyping people! If you are writing farce or satire then you need stereotypes, exaggerated types - but otherwise avoid them at all costs. So the next job is to make the character unique in some aspect. What might this uniqueness consist of? A bad habit, an unusual life experience, an ability or disability? We'll come to these details next.

The character must also share something with all of us, he or she must have some universal characteristics, or it's very difficult for the reader to have any empathy with them, to enable the reader to understand them. Universal characteristics are doing things like laughing, crying, eating and sleeping at the right moments. If the character doesn't do these things they appear inhuman - but that's not a bad thing if they are a super-villain.

Archetypes - these are original, but recognisable characters. They are the final goal, giving the reader a sense of familiarity with the character that will make them seem real, but a sense of newness that will make them different and original.

The Details of Character

What sort of details make for strong characters?

Consistency - people are not consistent, but your characters need to display a certain type of consistency on the page, or your need to give us reasons why they don't. If the mild-mannered schoolboy goes crazy and shoots someone, then you have to tell us why. Don't leave the reader thinking... 'What...!? Yeah, right!'

The past - a character's past makes a huge difference to how we see them, it gives us an insight into motive. The trick is communicating a character's past neatly. One way is to let another character establish their reputation, or imply aspects of their past. Other ways include flashback scenes, memories recalled either internally, or spoken to another character.

People behave in different ways with different groups of people - at work, at home, with friends - the changes make them interesting. And real. But remember point one, consistency - you have to do this carefully.

Attitude - give your characters an attitude, make them react to what's going on around them.

Habits - try and give each character at least one habit that can reoccur every time we see them. It will allow the reader to remember them more easily.

Talents - any special talent will make the character more interesting, whether they are a famous painter, or can sink a pint in world record time.

Tastes - any preference for something - beer, cheese, dogs, music - will also help fix the character in the reader's mind, and help them identify with them.

Appearance - it is easy to start with this, but it's actually the least important - many great fictional characters are never described.

Sources of Character Ideas

Where might we find inspiration for our characters?

Look inside - use aspects of your own character to make fictional characters come alive.

Life - just look around you, sit in a shopping centre or cafe with a notebook.

People you know - risky, but valuable so long as you are selective and ensure that other aspects of their character make them hard to identify.

News

Google

Social Media

Library

The Most Important Characters

Choosing a Protagonist and an Antagonist

Does the protagonist have to be likeable?

The protagonist must be compelling, fascinating or at the very least interesting, understandable and consistent, or believably inconsistent.

The journey - a story will be much more satisfying if the reader can see that the protagonist has a character arc, that they learn and change, and become better people as a result of the action in the story.

The protagonist needs an opposition force - sometimes this is another person, the bad guy.

The villain can often be more straight-forward than the hero, readers often prefer their bad guys simple to understand.

The bad guy must appear stronger than the protagonist, otherwise, there is little sense of jeopardy.

The Rest of the Cast List

The story will suggest the rest of the cast list to you - once you have your idea, and you have a line of action, a protagonist and antagonist, then start the story rolling. The other characters will just emerge as you write - but bear in mind:

There are major characters, minor characters, and walk-ons - spend the right proportion of time on their characterisation. Don't give us three pages of background on someone who gets killed a page later.

Keep notes on all your characters - otherwise you can spend hours trying to find the eye colour of a minor character, or worse, you can change it and not notice.

It's not the absolute amount of characterisation that's important, but the relative amounts. If you are writing a genre thriller the protagonist might only justify a couple of pages of character detail, with just a single line about a walk- on character. But if you are writing literary fiction, then you might need two pages for the walk-on character.

It comes to mind...

The Volvo Ocean Race is over, and I’ve just delivered my final Strategic Review for the website. It was an incredible finish with three boats tied on equal points going into the final leg. It all came down to one final strategic decision.

It wasn’t a breakdown, an injury, a random cloud or a speed edge that settled it at the death – although those things and many others had all played their part in getting it to that point. It was the answer to the simple, game-defining question of all ocean racing; “which way are we going here?”

The answer to that question was particularly acute for the leader, MAPFRE. They were in the nightmare scenario; the two competitors for the overall title were safely behind them, and then the two boats split and went opposite ways on the last leg.

And those opposite ways required total commitment, because the two routes were divided by several exclusion zones that they were not allowed to enter. They had to make a choice, and once committed, it was final. All they could do was watch it play out, and try and go as fast as they could.

MAPFRE were a comfortable two miles and change in front of the second placed boat, Dongfeng Race Team when the Dutch title contender – Team Brunel – made her move to go the other way.

MAPFRE had to make a decision and do it fast; stay as they were and continue to cover Dongfeng Race Team, or change course and cover Team Brunel. No doubt they reworked the calculations of time, distance and the predicted weather on each route many times to try to decide… but I suspect there was some psychology involved as well.

They had been chasing Dongfeng for the whole leg until passing them a few hours previously. They could be forgiven for thinking that they had put them away, that they were beaten.

In contrast, they had in turn been chased and closed down by Team Brunel for most of the leg, and not just this leg, but for most of the last four legs. Team Brunel were the form boat, winners of three of four of the previous legs. Worse, they had sailed past MAPFRE in the last few miles of the previous leg in a spot not far from where they were now.

The memory of that pass could have weighed very heavily on MAPFRE’s decision making process. It might even have been decisive, even if no one ever voiced it in the discussion that must have gone on onboard. I’ve written a fair bit recently on the impact of cognitive bias in decision making – looking at the systematically flawed judgements that human beings are hard-wired to make.

A famous discovery by the pioneers in this field –Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman – was a bias called the availability heuristic; a predisposition to judge the frequency of an event based on how readily or available an example comes to mind. In trying to estimate how often something happens and therefore what the risk is — and how best to respond to that risk — people simply report the ease with which they can think of an example.

So if you ask someone in California to judge the risk of losing their home from an earthquake – and whether or not they should buy insurance – they will assess the risk as a lot higher the week after news of a big quake in China, than at the end of a couple of years with no newsworthy earthquake events.

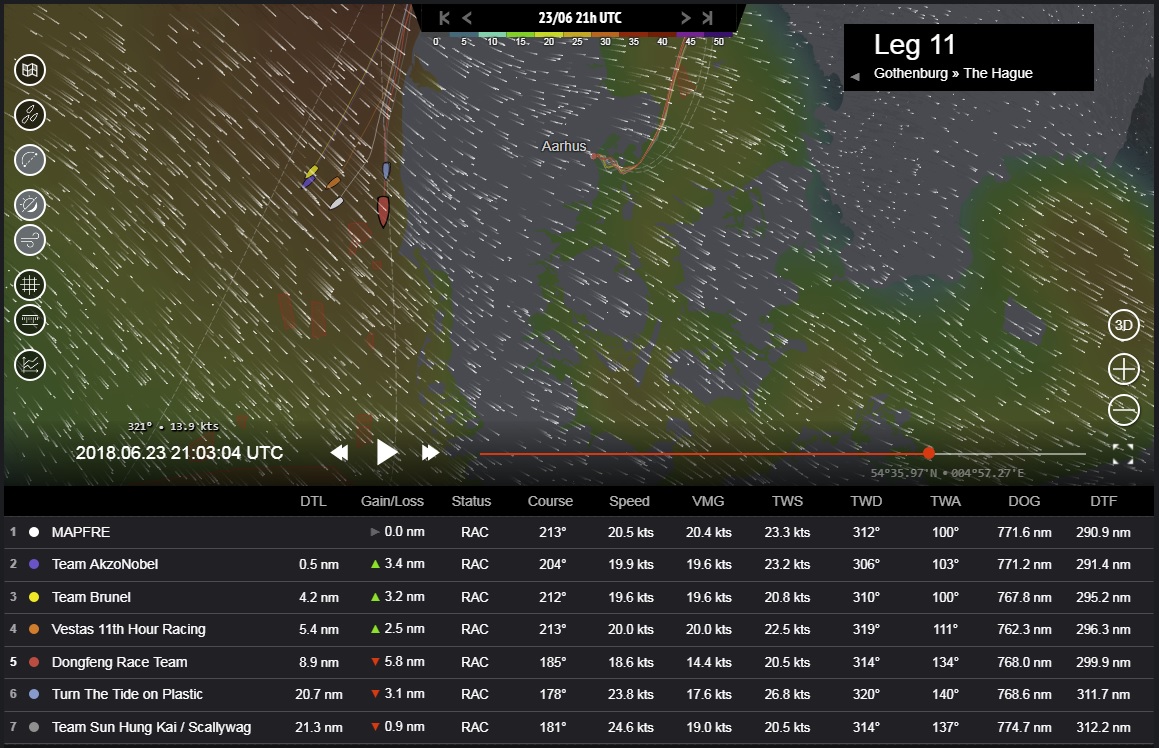

MAPFRE (white) change course to go the western route with Dutch title contender Team Brunel (yellow).

t must have seemed to those onboard MAPFRE that Team Brunel were the greater risk. They had just been passed by them in the previous leg of the race. And it looked like it was going to happen again. They changed their strategy at the last minute to go with the Dutch boat.

And then they had to watch as Dongfeng Race Team came out in front of both of them to take the Volvo Ocean Race with a final leg win. It’s even more painful to record – from MAPFRE’s point of view – that when you look at the data, it appears that MAPFRE would have won whatever they had done, so long as they hadn’t changed their mind. The losses they took in the late change of strategy (covered more distance, did more sail changes and manoeuvres) was about the same as Dongfeng’s gain…

Sometimes, it’s not the decision that counts, it’s making the decision in a timely manner. MAPFRE had the Volvo Ocean Race trophy in the palm of their hands. All they had to do to close their fingers around it was make their minds up early, offshore or inshore? If they had committed to either route early, it’s very likely that they would have won. It was the late change of heart that cost them the title.

Only they know what drove them to change their strategy, but I’d wager a few pounds on the fact that the memory of Team Brunel’s pass in the previous leg was involved. Lesson? When you’re making decisions stick to the facts, not the feelings from the most recent experience.

The Role of Luck – Part 2

The previous blog was about the role of luck in sport, one of several I’ve written recently on the impact of cognitive bias in decision making – looking at the systematically flawed judgements that human beings are hard-wired to make.

The out-take from that last blog was to accept that luck happens -- call it what it is and don’t make poor decisions going forward because you preferred not to believe that someone got lucky.

I’m writing a regular commentary for the Volvo Ocean Race (VOR) and used an example from the fourth leg of that event in the story, so I was particularly chuffed to see this post from Simon Fisher, the navigator on board Vestas 11th Hour Racing, a competitor in the VOR and currently racing in Leg 7.

“Ourselves and TTTOP [Turn the Tide on Plastic, another competitor in the race] just pulled off a nice ‘buffalo girls’ move as the rest of the fleet parked in a cloud. Lucky, but well executed!" Ah, the old buffalo gals move… The reference is to the line “Buffalo gal go around the outside” from the 1982 Malcolm McLaren hit, Buffalo gals.

If you check out the picture below you will see what Fisher is referring to – the lead four boats MAPFRE (white), Dongfeng Race Team (red), Team Brunel (yellow) and Team AkzoNobel (purple) have hit light winds under a cloud and stopped. The boats following their line and coming up from behind – Turn the Tide on Plastic (light blue) and Fisher’s Vestas 11th Hour Racing (orange) – have taken a little swerve and sailed around the outside of their almost stationary opponents to steal a handy five mile lead.

©Geovoile

Nice work if you can get it, and all down to luck. The boats ahead couldn’t have anticipated the lack of wind under the cloud, but the boats behind could -- they saw the parking lot in front of them. All they had to do was to steer up and go around the windless hole.

Applause and plaudits for Simon Fisher for calling it what it was; “Lucky” -- albeit with the proviso, “but well executed!” Sometimes we just can’t help ourselves…

The Role of Luck

I’ve been writing for a while on the impact of cognitive bias in decision making – looking at the systematically flawed judgements that human beings are hard-wired to make. And working as a commentator and strategic analyst for the Volvo Ocean Race is certainly throwing up plenty of meaty examples as seven boats try to deal with the vicissitudes imposed on their round the world odyssey by oceanic weather and currents.

My most recent Strategic Review explained how – as the fleet exited the Doldrums – the Hong Kong entry, Team Sun Hung Kai / Scallywag went from 80 miles behind to 80 miles in front. They did it by watching the leaders sail into a hole, and then swerving around it.

In contrast the overall race leader MAPFRE – skippered by Xabi Fernandez – came off worst of the lead group. Boats sailed away from them on either side leaving them with a 175 nautical mile deficit to the leader.

The moment when it all went right for Scallywag and wrong for MAPFRE ©Geovoile

I’m not going to take anything away from the girls and boys on Scallywag: the weather presented them with an opportunity and they grabbed it with both hands. However, the inescapable truth is that they would never have got that opportunity if they hadn’t been so far behind. And they got that far behind by almost hitting a reef that they saw at the last minute, subsequently taking a fifty mile detour to get around it...

Sometimes, luck does play a role in sport (as in life) and the trick is not to get fooled into making some poor decisions because of it. Football is a great example, in their 2013 book, The Numbers Game, Chris Anderson and David Sally established convincingly that luck was at least 50% of the result of any top flight game of football. So everything else, all the sound and fury surrounding players, managers, transfers, tactics, strategy... all taken together, in summation, has barely equivalent impact on the final result of any given game than… chance.

This doesn’t mean that we should stop bothering about all those things; far from it, even if we can only impact 50% of the outcome through our actions, we can still have an impact – but the really important point is that ignoring the role of luck can lead to some serious errors.

This partly relates to our need for narrative. When a sequence of events occurs, our predisposition, or our cognitive bias is to look for a causal reason, a story to tell about them. So when a player or a team put together a string of particularly bad or good performances or results, we tend to look for an explanation, any explanation other than luck.

Any decisions based on this explanation will likely turn out badly, because luck was the source all along. And this is because of a thing called regression to the mean. Any athlete in any sport has a base or mean level of performance. It might be measurable, for instance strikers will score a number of goals each season and this will average out at a particular number per game. Actual performances on any given day will vary around this number; there will be good days and there will be bad days, and a lot of the difference will come down to luck. Whatever else happens, at some point, the performances will regress back to the mean.

So the problem arises when an athlete or team hits a particularly rich — or poor — and extended run of form. We might start to mistake this for a permanent shift in the mean; we might put it down to a change in coaching, technique, diet or attitude. And we might make a decision — like buying a footballer for £50 million — based on this perceived shift in the mean. Only to discover when the player is turning out for our team, that the luck has dried up and the performances have regressed to the mean. And our £50 million player is now only worth £20 million again.

I don’t think anyone has ever done an Anderson and Sally-style analysis on how much luck is involved in ocean racing, but I can tell you from experience that it’s a lot. And the trick is exactly the same: don’t get fooled into wrong decisions because you didn’t account for luck.

MAPFRE and Xabi Fernandez got hit the hardest by the role of the dice that propelled Scallywag into the lead. They ended up back in fifth with that massive deficit after getting trapped in the light winds of the Doldrums for an extra 14 hours. They need to keep this in perspective - it was a crap shoot, they were doing all the right things and got unlucky... so don’t change anything.

I know Fernandez a little from his time with Land Rover BAR, and he’s a remarkable individual with an extraordinary amount of experience at the very top level – and an Olympic gold and silver medal to prove it. If you’re interested, then check out the profile I did when he was with the America’s Cup team.

From what I know of him, I’d say he will keep making level-headed, rational decisions – but history will weigh heavily on his soul. In the 2011-12 Race he was aboard Telefónica when they won the first three legs, before slowly fading from contention in the second half of the race.

It must have been a painful experience, and Fernandez will not want to repeat it. Regret is a powerful motivator that can often drive unnecessary change, as people seek to avoid the mistakes of the past.

It will be interesting to see how Fernandez and the MAPFRE team react once they’re across the finish line in Hong Kong. My money is on Xabi staying cool and carrying on with the strategy that has got them the overall lead, but you can never count out cognitive bias...

Loss Aversion and Changing Lanes

In the past couple of blogs I’ve been looking at the impact of cognitive bias on decision making in the Volvo Ocean Race . But you don’t have to tackle the Atlantic or the Southern Ocean to see the impact of these biases in our thinking. I got caught out by a classic cognitive bias this morning in the inevitable traffic jam that is the M27 on the daily commute.

We all know how this works. All three lanes of the motorway are slow for no visible reason, except that there are just too many people and cars for the available tarmac. Suck it up… except that the lane next to you seems to be that little bit less slow than the one you are in. So you change lanes. Oh dear. The new lane grinds to a halt, the old lane almost immediately accelerates and you lose.

So much, so familiar – despite knowing about the 1999 study by Robert Tibshirani and Donald Redelmeier that established that switching lanes rarely if ever gets you there faster, I still do it. Never mind the fact that it’s dangerous, and slows down the overall movement of traffic on the road (i.e. it screws everyone else which actually makes it a Prisoner’s Dilemma decision, but we’ll come back to that some either time – or read The Defector).

One of the reasons is loss aversion. We looked at this in my last blog – the idea established by psychologists that our dislike of losing something is about twice as strong as the love of gaining it.

This concept is often demonstrated with a simple bet — I’ll toss a coin, if it’s ‘tails’ you pay me £10. The question is, how much would I have to offer you for a ‘heads’, to get you to take the bet? When it’s tested on large groups the answer is usually around £20. People need to have a chance to win double what they could lose to take a 50/50 bet like a coin toss.

So every time you see a car go past you in a traffic jam, the sense of loss is twice as painful as the gain you feel that you have made when your lane is quicker, and you go past a car. In fact, if loss aversion is working as the psychologists predict, you could be gaining at a 2:1 rate in that queue and still feel like you’re getting hammered.

Think about it the next time you feel compelled to changes lanes – it’s not quicker, its dangerous, and it slows everyone down. It’s just making you feel bad.

Loss aversion and overconfidence

On Monday I wrote a strategy and weather review story for the start of the third leg of this year’s Volvo Ocean Race, called Into the Storm Track. A massive storm was forecast to develop and slam into the fleet, a forecast that’s becoming all too real as we can see in the image from the race website.

copyright Geovoile and Volvo Ocean Race

The big purple patch on the left is an area of storm force winds in excess of 60 knots, and it will overtake the fleet (represented by the little coloured boats) sometime this evening. I don’t want to get deep into the weeds of the weather and race strategy here as that’s not what this blog is about; let’s just say that all through the last couple of days there have been opportunities to get north where conditions are expected to be less intense.

The downside of going north was that it was a detour – more miles, and losses to anyone that stayed south. It was a balance of risk management – that’s a big, dangerous storm – versus speed and performance. Only two of the boats in the fleet took the opportunity to get north, you can just pick them out in the image, the light blue and orange boats. The rest have all stayed south... why?

I introduced the idea of cognitive bias in my last blog and I think this is another example of powerful biases at work in the human mind. The first and probably the most important is a thing called Loss Aversion. People hate losses — psychologists have shown that the dislike of losing something is about twice as strong as the love of gaining it.

Loss aversion is often demonstrated with a simple bet — I’ll toss a coin, if it’s ‘tails’ you pay me £10. The question is, how much would I have to offer you for a ‘heads’, to get you to take the bet? When it’s tested on large groups the answer is usually around £20. People need to have a chance to win double what they could lose to take a 50/50 bet like a coin toss. I think we’re pretty safe in concluding that not taking the loss has been a powerful motivator for those boats that have stuck to the southerly route.

The second cognitive bias at work here is overconfidence; it’s all pervasive in human society in general and sport in particular. Despite divorce rates averaging 50% in modern western societies, no one walking up the aisle believes they have at best a two to one chance of making it ‘till death do us part’.

It’s well known that small businesses, particularly restaurants and cafes have similar failure rates, but no one who stakes their life savings and a massive loan to open a cafe seems to really believe that they are betting everything on the toss of a coin.

Overconfidence is responsible for so many foul-ups in sport it’s hard to know where to start; everything from playing the long debunked long-ball game in football, to snap-shooting from 35 yards out and even trying to score from a corner (very low probability despite what the match commentary team will tell you).

It could be that those teams that have hung on in the south to avoid making losses are also overconfident about their ability to ride out the storm and take what’s coming. Maybe they will, maybe they won't - only time will tell, but what we can be sure of is that the route choices are unlikely to have been completely rational. Kind of scary when you look at the size and violence of that monster.

The Status Quo Bias

I guess the workings of the human mind have been a theme of my writing for a while, and apart from Game Theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma (used in my novel The Defector), I’ve been fascinated by behavioural economics – an area of research for which Richard Thaler just won a Nobel Prize.

The basic idea is that human beings are hard-wired to make mistakes, a whole category of errors that psychologists call cognitive biases — systematically flawed judgements that are a consequence of ingrained ways of thinking.

These psychological biases are the foundations of Thaler’s work in behavioural economics, a revolutionary new way of looking at how real people function in the complex world of money, incentive and human fallibility – it’s a topic popularised by the Freakonomics books written by journalist Stephen Dubner and economist Steven Levitt.

Michael Lewis famously and unknowingly revealed a cognitive bias when he told the story of Billy Beane, General Manager of the Oakland A’s, one of San Francisco’s two Major League Baseball teams. Moneyball was Lewis’s bestselling account of how Beane used Big Data to help the A’s, one of the poorest teams in the Majors, to beat bigger, richer teams relying on traditional talent scouts.

The problem that Lewis described in Moneyball is called representativeness; in that instance, it was judging athletes by appearance, by old school scouting, instead of assessing performance objectively by data analysis. Lewis was unaware when he wrote Moneyball that psychologists had already identified and named this judgement or cognitive bias.

Michael Lewis corrected this error with The Undoing Project, a book about two Israeli psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. They wrote the original academic paper on representativeness, and Kahneman later won a Nobel Prize for this work – but representativeness is just one in a long list of ways that humans fail to make rational judgements – identified by Kahneman, Tversky and their intellectual heirs.

I see cognitive bias everywhere; and at the moment it’s particularly evident in the strategic decisions made in the Volvo Ocean Race – and yesterday’s action was a good example. The second half of my story about it describes a window of opportunity to make a radical departure from the traditional strategy for tackling the South Atlantic. The chance was there for someone to split from the fleet, and maybe win the leg by half a day. No one took it. This afternoon, the 14th November they all remain in line astern, following each other south, with the leaders extending as they slowly sail into better breeze.

If you know anything about racing sailboats, you will know how hard it is to overtake from directly behind someone – passing requires leverage, getting out to one side, and finding an advantage in some different weather. Not one of the seven boats in the race took the opportunity to get that leverage and find that weather. Sure, it was a risk, a big risk – but some of these boats are trailing by 60-70 miles, they aren’t as quick as the leaders and the only way they are going to get on the podium is by doing something different. Or smarter. But the status quo bias is strong in humans, we exhibit a profound preference for things the way that they are. So… they all carry on into the South Atlantic in a neat and tidy line.

It may be that this wasn’t the right opportunity, that there was too much risk involved in backing the conclusions of a 12 day weather forecast… but still, there aren’t that many times when these opportunities will come about, and this might just have been a good one gone begging.

copyright Expedition

Back to the Spanish Castle

I’ve done a few stories for the guys at the Volvo Ocean Race over the last few years, some leg previews and technical pieces about the boats, but this week was the first time that I’ve returned to the Ten Zulu territory for the Volvo Ocean Race website. The Ten Zulu was a tactical and strategic commentary on the 2008-09 Volvo Ocean Race that was published daily at 10:00UTC, or Ten Zulu in aviation parlance.

It turned out to be quite a marathon, about 1500 words a day of detailed weather and strategic analysis for about 95% of the days they were out on the water. There were also live blogs for the finishes, commentary for the tv on the starts, and travelling to the ports to do the interviews for the book Spanish Castle to White Night.

Now, older, wiser and with two young children and an (albeit part-time) day job, I’m just doing occasional pieces on the key moments of the long legs, and reviews of the short legs -- opening with this strategic review of Leg 1. It’s similar to something I did for B&G (a blog slot now held by Libby Greenhalgh) for the 2014-15 race, but it’s great to be back writing about the race on the main website.

The leg previews on volvooceanrace.com are also my work, and having written these for several editions, I wanted to take a different approach. This time around I made it all about the transitions between the global weather patterns. These transitions dominate the strategy for each leg and I wanted to make this much clearer and upfront – see what you think, here’s the one for Leg 2... I’d love to hear any thoughts over on my Facebook page.

A half century for the 100 in Hamble

I can remember the moment when my wife Tina came bouncing into the room to tell me about the 100 in Hamble. It was a simple idea and immediately engaging – take a picture of 100 women, aged nought (i.e. a newborn) to 99 or from one to a hundred and all living in the village of Hamble.

We had a long discussion about whether the pictures should be done in the studio or at another location – perhaps connected to the individual – and eventually decided that consistency and simplicity would be best: black and white portraits shot in the studio to allow the individual faces to stand out against a white background.

And that was as far as we got. We had two children, and that occupied all our energy for several years. And then in 2016 Tina suffered from Encephalitis, a rare condition of brain inflammation that is fatal for one in ten sufferers. One consequence is memory loss and for a few hours when her condition was critical, she didn’t recognise me, wasn’t sure how many children she had, their ages or names.

One year old Molly Lambert got the 100 in Hamble started...

Since that time, she has been fortunate to have a strong recovery, and once she returned to work a few months after getting out of hospital, the idea of the 100 in Hamble resurfaced. A project about memories seemed the perfect way to recover memory, allowing her to reconnect with the village and the people in it. The story of the 100 in Hamble is also the story of Tina’s recovery.

Since then, fifty women have come to the studio, had their picture taken by Tina and spoken to her about their lives and their time in the village. I’ve written up each of those interviews, and posted the pictures to a website that we built for the purpose.

All the women have a story to tell, some ordinary, some exceptional, their individual lives revealing the history of the village through its people.

We’re only half way but it already strikes me that we’re building an unusual record in both words and pictures. The passing of the years is most clearly visible in the images, but the words tell their own story, they lead to so many trains of thought.

Here’s one: I had no idea that medical advice for women after childbirth in the early 1940s was to stay in bed for two weeks. It wasn’t easy to comply when the city was being blitzed by the Luftwaffe and the only relatively safe haven was the bomb shelter in the garden. She had to be carried there by the landlord from the pub opposite, while her Mum carried the baby.

So far, two Hamble women have told us about being bombed out of their homes. It’s easy to forget that this is the lived experience of people still amongst us. We don’t just watch it on the news, happening to other people. It happened here, and it could happen again.

It's the story of one village, but it could be the story of any small community in England, tracing through imagery and words the changes wrought by age, by industrialisation, two world wars and the coming of the information age. A story told through the lives and faces of ordinary women – sisters, mothers, friends, aunts and great-great grandmothers.

It’s been a remarkable journey, particularly because I’ve taken it with my amazing wife, watching her slowly get stronger, recovering memory, concentration, skills and stamina, and coming to terms with what’s happened. These are remarkable photos by a remarkable lady. I can’t wait to get started on the second half.

Three years and counting... down

I've now been with Land Rover BAR for over three years, telling the story of the quest to #bringthecuphome. It's been a long journey from the early days in a light industrial unit in Whiteley to the current waterfront perch in Portsmouth -- and of course for most of the team, the Cup village in Bermuda.

There is now a week and loose change before the first race of the 35th America's Cup Qualifiers, and the level of activity has been at this same frenzied pitch for most if not all of those three years. In just a few days we will learn whether or not we closed the gap to the established teams - Oracle Team USA, ETNZ and Artemis - who all came into this with, at the very least a team structure and in some cases a full-blown team and guaranteed funding.

Land Rover BAR came into this world with none of those things, and has built them all from the ground up. It's been a hell of chase to catch up, and we know we're close. The question is whether or not we're close enough to make it a yacht race. The boys can win this thing, if we're racing them. We'll know in a week.

Meanwhile, my job is to keep telling the story, which feels strange, after so many years of being on the front lines with Cup teams. But if there's anything I learned in all those years of navigating, when all hell breaks loose stay focused on your own job, and let other people worry about theirs. So I'm really pleased that in these final weeks, we're putting out some of my favourite stories from these past few years - Insight Profiles of both Giles Scott, and Xabi Fernandez - with more and better to come next week.

And after that I'll be back on the live blog - yup, after ten years, I'll be dusting off the tack-by-tack speed typing skills and returning to my first, post-sailing team Cup job... hope you'll join me this time next week, you can find it on the Land Rover BAR home page.

Fake news and the erosion of social capital

Fake new has been a popular topic for a while, and with a General Election now looming in the UK, I’m sure it’s going to become an even more pressing issue. There’s now a failure of consensus on what’s fact; never mind what’s right or wrong.

Don’t expect Facebook and Google to do anything truly useful about it. While it’s good for business, it will go unchecked. In Hitler’s Germany, big business largely went with the flow. Hitler was good for business, so business was good to Hitler. The market will never sort this out -- but just as technology can erode social capital and social trust, it can also build it.

eBay and even Amazon use technology to build trust, Facebook is using technology to destroy it. So let’s support the places that are building trust.

Hidden Figures and Seeing Infinity

A cracking review on Slate's Culture Gabfest and a theme of female and racial empowerment was enough for my wife and I to chose Hidden Figures; our first trip to the cinema since our eldest was born three and a half years ago. It was an excellent choice, this is a startlingly good movie, beautifully played by all the leads with a terrific script and couple of moments that would move any right-thinking person to tears.

If there was ever a time and a place when a meritocracy needed no boundaries, it was NASA in the 1960s as the Americans battled to catch up with a Russian lead in the space race. This tale of the slow and difficult rise through NASA’s hierarchy of Dorothy, and her fellow African-American mathematicians and engineers, was testimony to just how deep the racism went, and testimony to how far we have now come.

All of which makes me want to punch Donald Trump and his cronies for the threat he poses to that progress. This is a timely film, so it’s perhaps no surprise – given the propensity of movies to arrive in pairs like Tornado films, Meteorite films... that there’s another celluloid tale of racial empowerment out there. Hidden Figures was so good, that I was downloading The Man Who Knew Infinity andracking it up for Saturday night at the movies almost as soon as I heard about it.

This is a the tale of an Indian mathematician with remarkable intuitive insight to some of the most intractable problems of his day. Set in the early part of the 19th century, there really no shortage of racism or resistance to his arrival at Trinity College and application for a Fellowship there.

Unfortunately, it suffered in comparison to Hidden Figures. Dev Patel and Jeremy Irons do a good job with the material, but the lack of an urgent challenge – like the Russian’s putting an astronaut into space – left the film feeling soggy.

There was plenty of drama in Srinivasa Ramanujan’s life, but the way the film was structured left me wondering just what was at stake in his ideas. The pacing also front-loaded the sadness and tragedy, delivering little respite until the very end. And the motives of several characters – particularly the evil mother – were left unexplained. It’s a great story, but so much more could have been done with it.

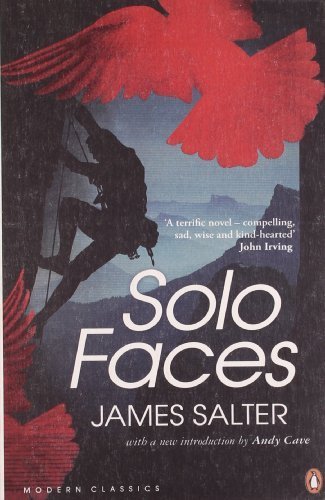

Solo Faces

I read about James Salter through other reviews of Bill Finnegan’s Barbarian Days, the subject of my last blog. Salter was a highly regarded stylist of his era, but seems to have never achieved quite the same general recognition of some his peers – John Updike, Richard Ford, Jack Kerouac or Norman Mailer.

What interested me is that Salter wrote books about action. He started out as a fighter pilot, flying more than a hundred combat missions over Korea in the early 1950s. His first novel was about these experiences and was subsequently made into a film, The Hunters starring Robert Michum and Robert Wagner.

He resigned from the Air Force to pursue a career as a writer, and much of his subsequent work deals with sport, adventure and physical endeavour. These are themes of much of my own work, and I’m always interested to see such action portrayed.

Salter would appear to have been influenced by the grand old man of literary action, Ernest Hemingway, with short sentences and very little dialogue attribution (sometimes too little to read clearly and easily). It’s not my thing, but it’s very effective when done well.

Solo Faces follows the fate of an American climber, Verne Rand as he departs hippy LA in the sixties for the much less forgiving snow and ice of the Alps. There he drifts, finally attempting a succession of notable climbs in pursuit of…. In pursuit of what?

This seems to be the question that Salter wants to answer – why do men do these things, take these risks? And – while I had issues with the arbitrary and spell-breaking shifts in viewpoint, the occasional racism and the role of women in this tale – Salter does get close to an answer worth reading.

Possibly the best surfing book ever?

I didn’t expect to find a surfing memoir via a podcast about American politics, but amongst all the gloom of the Slate Political Gabfest’s coverage of the last Presidential election cycle there was a recommendation to read Barbarian Days by Bill Finnegan. Soon afterwards, I heard that the book had won the 2016 William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award in the UK, having already picked up a Pulitzer for Biography. A surfing book? A Pulitzer? Really? The rebel alliance has clearly been sucked into the mainstream - this one obviously had to be read.

Bill Finnegan is a New Yorker staffer with a background in political and conflict reportage, so he knows his writing chops and has the contacts and reputation for this to come to the attention of the literary establishment in a way that most surfing books probably don’t. Having said that, this is the best book on the topic that I’ve read since Andy Martin’s Walking on Water, another minor masterpiece.

He never says as much, but Finnegan is a minor hellman, a big-wave surfer. Not the truly giant stuff taken on by household names like Laird Hamilton (ok, showing my age now) but still, this is a guy who has taken on most of the world’s best waves, including some of the heaviest. A man who has consistently surfed sessions in 10-15ft, often at breaks where reefs and rocks require complete commitment.

Very few of the people that can do this can also write as well as Finnegan, and the descriptions he brings back from the wave face and ‘out the back’ in big swells ring with a sonorous truth.

Bill Finnegan also captures the moment and the people beautifully, growing up in the 60s in LA and Hawaii, travelling cheap and light looking for waves in the 70s and 80s. I found myself constantly drawn back to this book, and to the water. The recent arrival of two children mean that it’s been a long while since I bothered to check the surf at the local breaks. I’m thinking that needs to change.

Pointless rants

Every now and again we all need to let off a bit of steam, and the only real question when you're in the mood for a modern-life-sucks rant is... who gets to be the target?

Could be the idiot motorcyclist who gave me the finger this morning for no other reason than my lane choice may have slowed up his arrival at his destination by about 15s.

But no, I get the fundamental stress of driving in south coast traffic.

So today it's all about kettles with useless spouts. Actually, not just useless spouts, but downright dangerous ones. Spouts and kettles that splash boiling hot water all over anything that happens to be within a foot of them.

What is it about kettle design? I mean, really, how hard is it to design a kettle with a spout that doesn't flood water all over the counter top every time you try to make a cup of tea?

There are only two components to good spout design, and it didn't take a three day consultancy with the computational fluid dynamics guys here at work to figure it out either:

1. A sharp edge at the point where the water breaks off from the spout and heads for the cup.

2. A concave shape to the exit ramp that the water flows down before it hits the aforementioned sharp edge.

That's it - and given modern plastic and metal moulding and pressing techniques you would think it would be just as easy to make a kettle with a good spout as a bad one... but apparently not.

So to all you kettle spout designers out there, and for that matter, teapot, milk and measuring jug designers too -- do the basics first, just make it pour well before you worry about what it looks like.

Ok, that's it. Nothing more to see here, move along quietly please.

Like being in the movie...

Losing your memory used to be something that happened in movies. Then it became something that happened to my mother, slowly, painfully slowly over two decades. Six weeks ago it became something that happened to my wife.

Six weeks ago I'd never heard of encephalitis. Six weeks ago I didn't know that flu-like symptoms followed by confusion were a dial 999 emergency. Six weeks ago my wife could remember who had given our children every single item of gifted toys and clothes. And then suddenly, after a few days of sickness, headaches and a horrifyingly frightening 48 hours of desperate confusion, she woke up and didn't even know or remember who I was.

I don't know if I will ever be able to bring myself to write about those six weeks. We talked about a book when she first started to pull out of it. What had happened and was happening to her seemed so far fetched and improbable it was surely a story that had to be told.

"This is like a first date," I said, as I explained that I was a writer. "No," she replied, "this is the flirting before the first date."

But now she's really getting better all that I want to do is to put it behind us and get back to normal.

An entry from the notebook - Point of View

These thoughts started out as notes to clarify my own thinking on the fundamentals of writing fiction. They developed a bit more of a structure when I taught a creative writing class at the local art gallery - it was a fun thing to do, but when the gallery closed the class did too and so I thought it was about time these notes found another outlet....

The Point of View (PoV) is the eye (or eyes) that the reader sees the story through - deciding on the viewpoint is one of the fundamental choices that you will make about your story.

The Different Points of View

Omniscient Narration - the writer tells the story, and can tell the reader whatever they want about the thoughts, actions and feelings of any character at any time.

• Advantages: flexibility, you will never get stuck unable to explain something, and you can show the reader how characters misunderstand each other - this can be really useful for comedy. It also allows the story to be told much more quickly - so if it's a saga or epic story, this is a good choice.

• Disadvantages: it can distance the reader and make it difficult to engage with any particular character. It's much more obvious to the reader that they are being told a story, and harder for them to feel within the story, that they are right there, experiencing it with the character.

A Single PoV - this is the opposite of Omniscient Narration. The story is told from the point of view of a single character. The reader only has access to the thoughts and feelings of one person.

• Advantages: it's very easy to engage with and feel empathy for the viewpoint character. If you want to provoke emotion in the reader (and you should) this is the best way to do it. The reader really experiences the story through this character.

• Disadvantage: the whole story must be visible through their eyes, and this can make plotting much more difficult.

Multiple PoV - the middle route between Omniscient Narration and Single PoV, where the story is told from the viewpoint of two or more characters.

• Advantages: plotting problems can always be solved by switching viewpoint, and it's still easy to engage with and feel empathy for the viewpoint characters, so long as you don't use too many.

• Disadvantages: it's harder to find a distinctive interior voice for several characters, and to control the writing so that they remain distinctive. It's also possible to confuse the reader, if they have to follow the experiences of too many characters. If you solve a plotting problem with a new viewpoint, then you will have to use that viewpoint elsewhere, it can't be there just for one scene.

A Rule

Use the absolute minimum number of viewpoints that you need to tell the story. There was a scene that I loved in Powder Burn that I had to cut, because it was the only scene from that characters point of view (another rule, kill your darlings). Funnily enough, it ended up in this blog too...